Advantages

To describe the benefits of technology, you need to compare it with something. In the case of full-featured 3D modeling, comparison is only possible with plaster in the articulator. But the differences are so striking that such a comparison would not be correct. A fully functional 3D model allows you to predict in real time changes in bite, TMJ shifts, and changes in facial features depending on the changes. Allows you to clearly see and evaluate the final result of treatment, and choose from several treatment options.

Full-featured 3D modeling technology is the latest and one of the most powerful diagnostic tools in modern dentistry.

Modeling stages

- Carrying out a 3D computer tomogram (3d CT) allows you to create a model of the bones of the skull and lower jaw. In our clinic, a CT scan is made measuring 16 by 14.5 cm, which allows us to make a model of both jaws, maxillary sinuses and both temporomandibular joints.

- Intraoral 3D scanning. Allows you to obtain a digital color 3D model of the dentition.

- Digital axiography. Allows you to obtain digital trajectories of movement of the lower jaw, comparing this trajectory with 3D CT, we obtain the trajectory of movement of the articular head of the TMJ.

- 3d model of a face. Several 10 photographs of your face are taken along different trajectories. Artificial intelligence creates a 3D face model based on photo data

- Electromyography and tens therapy allow you to assess the condition and “tension” of the muscles and make adjustments using TENS therapy.

Next, we use a software package with artificial intelligence to build a fully functional 3D model of the dental system. The program determines the position of the teeth from an intraoral 3D scan and superimposes this model on a computer tomogram model. Artificial intelligence identifies the lower jaw and virtually “separates” it from the skull. Superimposes the trajectory of movement of the lower jaw obtained by axiography onto the separated lower jaw and it begins to move along the resulting trajectory. After this, a 3D model of the face is added to this set of studies, and with the help of artificial intelligence we collect this set of studies into a single, fully functional 3D model.

What does a full-featured model mean, you ask? In our case, it allows us to digitally plan treatment. Let's say we have planned gnathological treatment and want to make a muscle relaxation mouthguard. With this fully functional model, we will be able to digitally evaluate the required parameters of the mouth guard, predict the effect on the joint, carry out treatment according to a digital protocol, and simply print the mouth guard on a 3D printer. All work will take no more than 2 days. Or we want to carry out total prosthetics and rehabilitation of teeth with generalized abrasion. We plan “new teeth (crowns, veneers, etc.)” using an intraoral 3D model of teeth, check for hypercontacts, print them on a 3D printer and receive temporary crowns almost on the day of the visit.

Models of the jaw - from antiquity to modern technology

January 15, 2013

| Arthur Machin, student of the Faculty of Medicine of RUDN University, specialty “Dentistry” | It is difficult to find a dentist who has specialized in the field of orthopedics, orthodontics or even dental surgery, much less a dental technician who would call his work convenient and his conclusions objective, if he did not have the opportunity to take an accurate impression of the dental relief at any time. row. An impression, followed by the construction of a model, allows us to easily assess the scale and nature of defects in the teeth and underlying periodontal areas and correctly plan the further course of action. Whether we are talking about creating a crown or a prosthesis, or correcting a bite right up to surgical intervention, the model of the jaw (or articulator) will be an integral part of the process. |

Orthopedic dental structures have been used by doctors for centuries. The earliest evidence of such was discovered during the opening of the pyramid of Pharaoh Khafre in 1807 in Egypt. The pharaoh who died 4,500 years ago was buried with his wooden dentures. A similar discovery was made during excavations in the city of Sidon, where the owner of the prototype of a modern bridge was buried with his property 2300 years ago. The Romans used gold, wood, bones and animal tusks for prosthetics. But all these designs were not entirely aesthetic and functional. The disadvantages of dentures were primarily due to the fact that the craftsmen did not have the opportunity to capture the relief of the patient’s teeth, and relatively accurate designs were created only through the talent and experience of the specialist himself.

It is also important to keep in mind that the people who created the dentures were not doctors, since dentistry was not considered a medical science. For a long time, their production was carried out by artisans: barbers, jewelers, blacksmiths and metal carvers. The skill of the artisans reached a significant level and was more developed than the methods of conservative dentistry of that time, but their knowledge of anatomy was not scientifically substantiated. The first who publicly proposed taking an impression of the jaw were the European dentists Poorman and Pfaff. In 1692, the Saxon dentist M.G. Purman captured the relief of a human jaw in wax and sealing wax, thereby obtaining the first impressions of the dentition. Pursuing a more complex goal, in 1756, the personal dentist of the Prussian king, Philipp Pfaff, closes the patient’s jaws with wax and takes a double-sided impression. Next, he fills the sealing wax with plaster and gets a model of closed jaws. Such experiments help him carefully examine the bite of patients after they leave. Interestingly, Praff is also credited with a patent for the use of impression trays for this purpose. The discoveries described above greatly influenced the development of orthopedic dentistry, and in 1764 Claude Mouton invented artificial crowns and clasps to fix fixed dentures. In 1788, the French pharmacist Duchateau and the surgeon Dubois de Cheman successfully used porcelain for this purpose.

This material combined aesthetics not inferior to ivory, a more affordable price and simplified technology for creating a prosthesis. The widespread use of porcelain has forced dentists to look for new materials that would allow them to take precise impressions of teeth more easily and efficiently. In 1840, they began to use impression plaster, which differed from its modeling type. Gutta-percha began to be widely used in 1848, and 8 years later, British dentist Charles Stent invented another similar mixture, calling it after himself. In the process of development of biological sciences, the properties of agaragar seaweed are revealed. This technology came to dentistry in 1925, providing the basis for the creation of alginate impression materials. This material (when used correctly) gave surprisingly accurate results, and the technique of its application was much more convenient. In the second half of the 20th century, more expensive silicone began to be used.

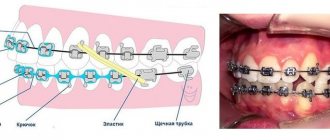

Associated dental devices that appear during the same period are articulators. Articulators are mechanical devices that are designed to reproduce the movement of the lower jaw relative to the upper jaw. Externally, they most often represent a metal structure that juxtaposes two plaster models of a human jaw against each other, thereby reproducing his bite and movements of the temporomandibular joint.

| The first who decided to achieve the reproduction of occlusion in practice was the previously mentioned Philip Pfaff, and his work was a success. In order to position jaw models movably against each other, in 1848 Joseph Linderer developed a wooden occluder. He took as a basis the experience of Tonn and Evans, who 8 years earlier created devices from perforated sheet metal. They consisted of an upper and lower part, connected to each other by a vertical screw, which made it possible to adjust the distance between them. The peculiarity of the invention was that the upper part could move not only vertically, but also horizontally. The first truly scientifically based articulator was developed in 1858 by F.A. Bonville, a dentist from Philadelphia. He equipped his device with a triangular frame, the dimensions of which were obtained by measuring thousands of mandibles. The measurements allowed him to obtain an equilateral triangle with a side of 105 mm, which helped position the jaw models symmetrically and equidistant from the temporomandibular joint. Bonville never patented his discoveries and made them a gift to all humanity. From this moment onwards, in the course of the development of the anatomy and physiology of the human dentofacial apparatus, more accurate articulators were created, many of which are used by us to this day. | The first scientifically based articulator, developed in 1858 by F.A. Bonville |

Finally, I should say a little about modernity. In the era of computer technology, a unique CAD/CAM technology was developed, the popularity of which is growing every day. This technology is designed to eliminate the human factor as much as possible in the process of planning and creating crowns and dentures. By scanning the dentition, the computer creates a three-dimensional model, from which the optimal crown structure is designed and then cut out on a milling machine. A CAD/CAM system can scan the dentition from a model of the jaw made by the doctor in advance. But modern intraoral scanners allow the most accurate scanning of the human jaw directly. As the technology becomes more affordable, it threatens to eliminate the need to create jaw models entirely.

see also

May 2, 2013

Long way home

Before the familiar toothpaste and brush appeared in every home, humanity did a tremendous amount of work.

July 17, 2012

In the history of hygiene, not everything is sterile. How modern disinfection began

The history of sterilization begins from the moment the first surgeon rubbed a stone or obsidian knife with a bunch of grass. Moreover, the point here is not in the surgeon and his knife, but in the tuft of grass that was used to wipe the instrument. After all, ancient people could only rely on practical experience. He ate this grass and his stomach went away; he ate that root and he died. Experience was accumulated and passed on from generation to generation. And that tuft of grass with which the surgeon wiped the knife could well have been plantain or chamomile.

March 12, 2012

How the instrument was tamed

Good modern equipment makes a trip to the dentist nothing more than a spa procedure. However, one can guess that everything began much less positively. Dentistry originated in the 5th millennium BC, and, as in any other field, complex technical mechanisms originated in the simplest solutions.

March 12, 2012

X-ray diagnostics in Russia

If you hold your hand between the discharge tube and the screen, you can see the dark shadows of the bones in the faint outlines of the shadow of the hand itself,” - this is how Wilhelm Conrad Roentgen described the new type of rays he discovered in 1895. Whether the scientist had any idea how large-scale the revolution in medicine that his discovery would cause would be, we don’t know. However, it is believed that it was with these words that modern x-ray diagnostics began. Return to section