Fused tooth roots are a fairly rare occurrence. According to statistics, they are detected in approximately 4% of patients who seek help from a dentist. Experts attribute the causes of the problem to:

- tooth dislocation,

- severe damage to the jaw,

- infection of the rudiment during eruption,

- violation of root resorption when changing teeth,

- long-term inflammation of soft tissues,

- genetic predisposition.

Find out if it's dangerous, what symptoms you shouldn't ignore, and how to treat it.

What could be the consequences?

The problem most often manifests itself exclusively from an aesthetic point of view - psychological problems arise, the patient wants to correct the pathology as quickly as possible, especially if it is pronounced. That is, if the teeth and gums are healthy, then such discomfort is the only consequence of the problem.

If the short size of the crowns is caused by an abnormal structure of the teeth, problems with the gums, or abrasion of the enamel, then the consequence of this condition may be inadequate chewing of food, which will inevitably lead to problems with the gastrointestinal tract, premature aging of the face and the appearance of deep wrinkles near the mouth, and general deterioration dental conditions and even their loss.

What are the dangers of fused tooth roots?

Most often, the roots of primary molars grow together. In such cases, treatment is usually not carried out. By the age of 5-6 years, the tissues dissolve. This process must be monitored to prevent displacement of the permanent rudiments and to avoid malocclusion.

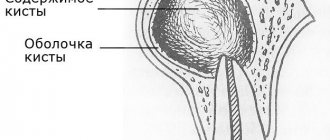

Often, dentists identify fused roots of wisdom teeth. They may not bother a person, but more often they cause discomfort. With this disorder, the risk of inflammation, the development of periodontal disease, and the formation of a cyst or granuloma increases.

Treatment methods

The treatment method for this pathology is selected based on the cause that caused it. If the teeth and gums are in good condition, then it will be enough to perform gum surgery or install veneers, which will lengthen the crown part. If inflammation is present, then the treatment tactics should be identical to the methods for solving the problem of periodontitis. In any case, a visual examination, diagnosis of the condition of teeth and gums, followed by the development of an individual rehabilitation plan will be required.

Trimming the labial frenulum The labial frenulum is usually very short, which results in exposed teeth. But in a number of situations, on the contrary, it can be excessively long and literally hangs over the crowns. In such a situation, the size of the crowns naturally becomes smaller. Plastic surgery of the frenulum will solve the problem - this involves cutting off part of the mucous membrane and suturing it. The procedure can be performed at almost any age. Local anesthesia is required.

Price:

5000 rubles more about the solution

Gumplasty The doctor visually lengthens the teeth by trimming the gums and changing the position of the gingival contour. The operation is only permissible on healthy gums and teeth. At the same time, it may be necessary to carry out a remineralization procedure, since the part of the teeth that is located under the gums is more susceptible to external mechanical influences. If a large volume of mucous membrane was trimmed, additional microprosthetics will be required using veneers or lumineers.

Price:

from 6,000 rubles more about the solution

Veneers and lumineers Thin onlays allow you to correct many aesthetic defects in the dentition. Microprostheses are created from ceramic composite, ceramics or zirconium dioxide. If you have short teeth, they allow you to change their height, but only in the front part of the row, since they will simply break off on the lateral chewing elements. Prosthetics are often combined with gingival contour plastic surgery.

Price:

from 15,000 rubles more about the solution

Additional roots and their clinical significance

Most mandibular molars have two roots (mesial and distal). But in some cases, the presence of an additional, third root is noted, which in turn must be taken into account when carrying out endodontic as well as orthodontic treatment, because moving teeth with three roots is much more difficult than with two. In addition, the process of removing three-rooted mandibular molars also requires individual skills and clinical experience.

Terminology

Radix entomolaris (RE): additional distal-lingual root Radix paramolaris (RP): additional mesio-buccal root.

The third root (lingual) of the lower molar was first described by Carabelli in 1844. Already in 1914-1915 Bolk gave additional roots a “name”: radix entomolaris or radix paramolaris, depending on their location.

Figure 1: Clinical photographs of extracted mandibular molars with accessory roots radix entomolaris or radix paramolaris A: First molar with radix entomolaris [distal lingual view (left), lingual view (right)] B: Radix entomolaris third molar (lingual view) C: First molar with separate radix paramolaris (buccal view). D: First molar with radix paramolaris (buccal view).

Etiology

The etiology of the formation of an additional root remains unclear. Obviously, their development may be associated with the influence of external factors during tooth formation, or with the influence of a separate atavistic gene, or changes in the human polygenetic system.

Prevalence

Radix entomolaris occurs in the first, second and third molars of the mandible, but is least common in the second molar. Moreover, the prevalence of radix entomolaris in the structure of the first molars of the lower jaw varies in different specific ethnic groups:

- African descent - approximately 3%

- Eurasian and Indian origin - 5-30%

- indigenous population of certain territories (Chinese, Eskimos, American Indians) - 5-30%.

Radix paramolaris is much less common than radix entomolaris, and most often in the third molars of the mandible (2%), but sometimes in the second molars.

Morphology

An additional mandibular molar root is almost always associated with the presence of additional cusps in the coronal part of the tooth (tuberculum paramolare). However, no feedback is observed, that is, an additional tubercle of a tooth is not always associated with the presence of an additional third root. Clinical examination of the tooth neck area using a probe allows the identification of a specific convexity, which is the beginning of a branch of an additional root. Additional roots can be represented by a separate morphological formation, or are often “fused” together with the main roots. The length of radix paramolaris and radix entomolaris varies from very short to those characteristic of ordinary roots. Although, most often the additional roots are shorter than the main ones (photo 4).

De Moor classifies the radix entomolaris depending on the curvature present:

- Type I: straight root canal

- Type II: An initially curved inlet that continues as a straight canal.

- Type III: Initial curved entrance with a second curve starting in the middle and continuing to the apical third.

Photo 2: Radix entomolaris in a lower first molar: three roots and four canals. The length of the additional distolingual root is comparable to the length of the main roots.

Photo 3A: Radix entomolaris in a lower first molar: three roots and five canals. The main distal root (DB) may have two canals (DB1 and DB2), as well as an additional root DL; in this case, DB1 and DB2 merged in the middle third of the DB root. The DL root was of comparable length to the other roots. A) X-ray before treatment.

Figure 3B: Post-obturation radiograph.

Photo 3C: Photograph of the pulp chamber showing MB, ML, DL and DB 1 and 2 in close proximity.

Figure 4: Radix entomolaris in a mandibular first molar with three roots and four canals. The distal lingual root is significantly shorter than the other roots.

X-ray and CBCT

Spot radiographs must be carefully examined to identify additional roots. In cases of radix entomolaris, the distal lingual root often lies in the same buccolingual plane as the main distal root. Such a graphic “overlay” can “hide” the root on the radiograph, and this is why it is important to use the principle of parallax (position the X-ray beam with a mesial or distal tilt of 30 degrees) when taking targeted images.

3D imaging using CBCT is also extremely useful for additional root verification and treatment planning. CBCT slice data can be considered as a “road map” for endodontic treatment, allowing preliminary localization of all areas that are difficult to reach for canal treatment (photo 5).

Figure 5A: CBCT helps determine the number of roots and canals. CBCT also makes it easier to visualize the extent and location of distolingual canal curvature to plan treatment accordingly. A) Periapical radiograph demonstrating the presence of three roots.

Figure 5B: CBCT findings (axial slice) confirming the presence of a distal-lingual root. The main distal root (DB) has an oval canal.

Figure 5C: CBCT image demonstrating curvature in the distal lingual root.

Figure 5D: Postoperative periapical radiograph.

Figure 5E: Spot radiograph after obturation

Clinical advice

A thorough clinical and radiological examination (as described above) is essential to identify radix entomolaris and radix paramolaris (Figure 6).

Figure 6A: Radix entomolaris in the mandibular first molar. Clinically, this tooth is characterized by the presence of an additional tubercle (tuberculum paramolare). When probing the cervical area of the tooth, a slight protrusion was identified, indicating the possibility of the potential presence of an additional root. The periapical radiograph shows the additional root (highlighted in blue).

Photo 6B

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of optical magnification and additional lighting in the endodontic treatment of teeth with complex morphology. The bottom of the pulp chamber is characterized by a darker shade. The dark dentinal lines present at the bottom represent a kind of “map” that helps the doctor identify the position of the mouth of all canals. For additional verification of the orifices, a long, sharp endodontic probe (DG16) can also be used. The access cavity must be expanded in the direction of the accessory canal (RE: distal-lingual, or RP: mesial-buccal). A bur with a non-sharp tip (such as an Endo-Z bur) may be useful for widening the orifice. Ultrasonic instruments can also be used for a similar purpose. The coronal part of the root canal in many cases is quite curved, so it is important to devote enough time and attention to the expansion stage of the coronal part of the canal, so as not to provoke the formation of a ledge (step). The author in his practice uses nickel-titanium rotary instruments (such as XA or SX from Dentsply Sirona) to treat the ostial part and coronal third of the root. After expanding the coronal part, they begin to form the carpet using small hand files (up to size 10). Given that the accessory root is often curved, it is best to avoid the use of instruments such as Gates Gliddens, which may cause perforation. Large hand files, being also quite rigid, can lead to transportation of the canal and apical foramen. In order to process additional canals of molars, it is best to use nickel-titanium instruments, which are distinguished by their flexibility. When working in canals, it is sometimes necessary to work with three different types of instruments in three different parts of the canal in order to achieve full patency. When working with instruments, especially rotary ones, it is important not to push them, as this movement can cause the formation of a step or fracture of the file. In cases of radix entomolaris, the main distal root (DB) may have two canals (DB1 and DB2) (Figure 5). DB2 is harder to find because it can "hide" on the isthmus between DB1 and DL. It is often located in close proximity to DB1. A thin ultrasonic instrument can be used to conservatively debride the isthmus while searching for an additional canal (Figure 7).

Photo 7A: Radix entomolaris LR6 with five channels: DB1, DB2, DL, MB, ML. A general dentist removed the pulp from the tooth and referred the patient for specialized root canal treatment due to the complex morphology of the endodontist. Radiographs were obtained at the stage of checking the fit of the master pins and after obturation. Canals DB1 and DB2 merge in the apical third.

Figure 7B: Clinical photographs of the distal pulp chamber after access and coronal expansion. Visualization of the mouth of the DB1 and DL canals.

Figure 7C: An isthmus was visualized between DB1 and DL and opened using a thin ultrasonic instrument. A separate channel, DB2, was located in close proximity to DB1.

Photo 7D: Photo after obturation.

Photo 7E: Final Photographs and Radiographs

Photo 7F: Final photographs and radiographs. The distal fissure was identified after the access was created. With microscopic magnification, it reached the mouth of the canal. No pathological pockets were identified in the periodontal structure, but the patient was informed of the compromised prognosis of this tooth. The tooth was restored using composite and orthodontic tape. In the future, the patient was recommended to have the tooth covered with a cusp-overlapping crown.

Conclusion

Mandibular molars have the potential to have an additional root, with the term "radix entomolarix" indicating the presence of an additional distolingual root and the term "radix paramolaris" indicating the presence of an additional mesiobuccal root. Endodontic treatment of accessory roots of lower molars is a more complex procedure than treatment of their main roots. In order to detail the morphological features, it is advisable to use targeted radiographs obtained taking into account the principle of parallax, as well as the capabilities of CBCT. Often the accessory root of the lower molars is shorter than the main ones, and is excessively narrow and curved. To avoid complications during access formation and processing of additional canals, the use of modified endodontic intervention techniques is required.

Posted by Creena Patel

The structure of baby teeth

A temporary bite differs from a permanent bite not only in the number of teeth (in a temporary bite there are 20). Baby teeth have a bluish tint to the crown, which is also much wider than the root. Children have less enamel mineralization, so caries affects them very quickly, and the pulp takes up more space compared to permanent teeth. The canals of baby teeth are wider, easier to pass for instrumentation, and the roots themselves have a rounded shape. The structural features of baby teeth determine their rapid destruction in case of infection penetration and very severe pain in the child, so in childhood, visit the dentist in a timely manner.

Knowing the structure of teeth will help you quickly find a common language with the dentist and feel more confident when discussing treatment issues.

You will be able to better navigate the manipulations performed by the doctor and clarify all the points that interest you with an understanding of the essence of what is happening. This article is for informational purposes only, please consult your doctor for details!