Salivary glands – increased salivation and dry mouth

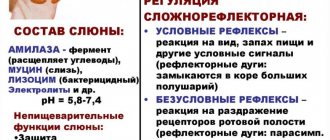

There are a number of tips to help keep

your salivary glands healthy:

First, you need to drink plenty of water. Secondly, you should use chewing gum that does not contain sugar. And thirdly, it is necessary to suck on lollipops, which also do not contain sugar.

In certain cases, your dentist may recommend gargling with artificial saliva. The above drug is sold in spray or liquid form. You do not need a prescription to purchase it, but use it several times a day. However, artificial saliva does not contain proteins, minerals and other necessary elements that are contained in natural salivary fluid. Thus, the above drug will simply be useless for digestion.

Excess saliva in the mouth

By and large, a large amount of saliva is not a problem if the condition is not systemic. Typically, the amount of saliva you produce depends on what you drink or eat. In a healthy person, the body easily eliminates excess salivation. In general, excessive salivation is caused by overactivity of the salivary glands, as well as if a person has a disturbed swallowing process.

If you eat a spicy dish during your lunch break, your body will begin to intensively secrete saliva. This is because the taste buds on the tongue help increase the volume of fluid produced. For a visual example, you can put something sharp on your tongue. After a few moments, you will be able to feel a rush of saliva into your mouth. Also, sour foods affect excessive salivation. Accordingly, you can reconsider your diet if you are concerned about excess salivary secretion. In addition, the above symptom may occur as a result of certain diseases and abnormalities, as well as due to the use of special medications.

Specific features of nausea and vomiting

To identify the cause of poor health and assess the patient's condition, the duration of nausea and vomiting is important. Acute vomiting (1-2 days) is often caused by medications, infections, poisoning (such as alcohol), kidney damage, and diabetes. Chronic vomiting (more than 1 week) is characteristic of long-term gastrointestinal diseases and mental disorders.

Features of vomiting and nausea

- Vomiting immediately after eating is characteristic of stomach lesions. If the gag reflex occurs 2-3 hours after eating, pathology of the duodenum is possible.

- Nausea and vomiting of acid are observed with gastritis with increased secretion and stomach ulcers.

- Vomiting of bile (greenish-yellow color) is caused by pathology of the hepatobiliary system (liver, gallbladder) or pancreas.

- Bloody vomit (red or brown) indicates gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Vomiting mucus is characteristic of diseases of the respiratory system (smoker's bronchitis), which occurs with a debilitating cough. Patients with alcoholism often complain of foamy vomiting in the morning (on an empty stomach).

- Vomiting with fever indicates the infectious nature of the disease. With a viral infection, the temperature can reach 39-40ºС. Nausea, vomiting and temperature up to 37.5-37.8ºС are more typical for bacterial infections.

- Vomiting with diarrhea/constipation without fever suggests an intolerance or allergy to certain nutrients, such as lactose.

- Constant nausea without vomiting and fatigue often occur with hypothyroidism.

- Vomiting and pain in the upper abdomen makes it necessary to exclude myocardial infarction, but is more often associated with gastrointestinal pathology.

- Fecal vomiting (dark vomit with a characteristic smell of feces) occurs with intestinal obstruction, tumors, and gastrointestinal fistulas.

Diseases that cause increased salivation

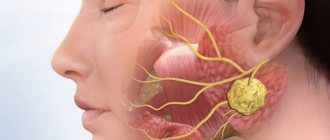

Experts note a number of diseases that cause our salivary glands to work hard. Among them: central and peripheral paralysis, gastroesophageal reflux disease, mental development disorders, abnormally large tongue, Parkinson's disease, pregnancy (severe toxicosis), poisoning, stroke, rabies.

In addition, there are a number of drugs that cause excess salivary fluid. These include: drugs against schizophrenia, antiepileptic drugs, as well as medications prescribed to patients undergoing radiotherapy. The common medical term for excess salivation is sialorrhea or hypersalivation.

Excess saliva, or how to prevent it

By and large, there are three types of therapy that are used to treat increased salivation. These include Botox injections, surgical treatment and medications that are available only by prescription. It all depends on the factors that caused the disease. It is clear that the simplest thing will be to prescribe certain medications. Typically, the above drugs will include scopolamine and glycopyrrolate. Side effects include increased heart rate, trouble urinating, drowsiness, and blurred vision.

For severe forms of drooling, specialists resort to Botox injections into the salivary glands (one or more). The treatment is considered safe, but its effect only lasts for several months. And only in very severe cases do doctors resort to surgery. During surgery, the salivary glands are removed or the direction of the excretory ducts is changed.

With the help of surgery, you can permanently get rid of increased salivation. Salivary glands – increased salivation and dry mouth

Chronic abdominal pain and irritable bowel syndrome

Abdominal pain has been and remains a serious problem in internal medicine and gastroenterology. The greatest difficulties arise when identifying the causes of chronic abdominal pain syndrome. Understanding the mechanisms underlying the formation of pain can partly help in establishing its cause and choosing a way to relieve it [2].

The appearance of pain is associated with activation of nociceptors located in the muscular wall of a hollow organ, in the capsules of parenchymal organs, in the mesentery and peritoneal lining of the posterior wall of the abdominal cavity, stretching, tension of the wall of a hollow organ, and muscle contractions. The mucous membrane of the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) does not have nociceptive receptors, so its damage does not cause pain. Inflammation and ischemia of the gastrointestinal tract through the release of biologically active substances (BAS): bradykinin, serotonin, histamine, prostaglandins, etc. lead to a change in the sensitivity threshold of sensory receptors or directly activate them. The same processes can provoke or aggravate spasm of intestinal smooth muscles, which in turn causes irritation of nociceptors and a sensation of pain. Signals from the intestine are transmitted along afferent fibers through the spinal ganglia and reach the anterior parts of the brain, where the sensation of pain is realized in the postcentral gyrus. Efferent fibers travel to the periphery and cause contraction and relaxation of smooth muscles and vasodilation. A large number of different neurons modulate pain perception and response.

In general, there are four main mechanisms for the formation of abdominal pain: visceral, parietal, radiating and psychogenic.

One of the variants of abdominal pain due to organic causes may be parietal pain arising from involvement of the peritoneum. It is mostly acute, clearly localized, accompanied by tension in the muscles of the abdominal wall, and intensifies with changes in body position and coughing.

The most common mechanism of abdominal pain is visceral pain, which is caused by increased pressure, stretching, tension, circulatory disorders in the internal organs and can be the result of both organic and functional diseases. The pain is usually dull, spastic, burning, and has no clear localization. It is often accompanied by a variety of vegetative manifestations: sweating, anxiety, nausea, vomiting, pallor. Due to the large number of synapses between neurons, double innervation often occurs, which underlies the radiating nature of pain. The latter is understood as the reflection of pain during an intense visceral impulse in the area of zones of increased skin sensitivity, at the site of projection of other organs innervated by the same segment of the spinal cord as the involved organ.

At the initial stages, organic diseases (appendicitis, diverticular disease, etc.) may be accompanied by visceral pain, then, in the case of inflammation of the peritoneum, parietal pain.

Psychogenic pain occurs in the absence of somatic causes and is caused by a deficiency of inhibitory factors and/or an increase in normal incoming afferent signals, due to damage to central control mechanisms and/or a decrease in the synthesis of BAS. The pain is constant, sharply reducing the quality of life, and is not associated with impaired motor skills, food intake, intestinal motility, defecation and other physiological processes.

In functional diseases, the mechanisms of pain formation are different and can be isolated or combined: visceral genesis is often combined with radiating and/or psychogenic mechanisms. The pain is mainly of a daytime nature and rarely occurs during sleep [4].

In practice, the likelihood of an organic cause underlying visceral pain is much greater in the presence of “anxiety” symptoms, which include: predominantly nocturnal pain, waking the patient from sleep; onset of symptoms after the age of 50; presence of cancer in the family; the patient has a fever; unmotivated weight loss; changes identified during direct examination of the patient (hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, etc.); changes in laboratory parameters of urine, feces and blood; changes identified through instrumental studies (stones in the biliary tract, colon diverticula, dilated common bile duct, etc.).

The attempt to differentiate abdominal pain using the least number of examinations, often traumatic for the patient, can be well illustrated by irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Despite the presence of the term “syndrome” in the name, this pathology refers to independent nosological forms. According to the World Gastroenterology Organization (WGO), IBS is a functional bowel disorder in which abdominal pain or discomfort is associated with bowel movements or changes in intestinal transit [20]. Associated symptoms may include bloating, rumbling, and defecation disorders. To make this diagnosis, according to the Rome III criteria, pain must be recurrent, present at least three days per month for the last three months or more, and be associated with at least two of the following three features: change after defecation, its occurrence must be associated with a change in frequency or stool shape. Symptoms must have bothered the patient for the last three months and first appeared six or more months ago [12]. IBS, like most other functional gastrointestinal diseases, is characterized by an increased level of depression, anxiety, and a tendency to hypochondria.

Abdominal pain in IBS is necessarily present, but depending on the prevailing disorders of intestinal passage, the following options are possible: IBS with diarrhea (frequency of loose stools more than 25% of the time, and dense stools less than 25%, more often in men), IBS with constipation (hard stool more than 25% of the time and, accordingly, liquid less than 25%, women are more likely to suffer), mixed or cyclic IBS (liquefied and solid stool more than 25%) [12, 20]. According to the WGO recommendations, it is possible to divide into subgroups depending on which symptoms dominate: IBS with a predominance of intestinal passage disorders, IBS with a predominance of pain, IBS with a predominance of bloating. And finally, according to the provoking factor, it is possible to subdivide the pathology into post-infectious IBS, food-induced IBS (or certain foods), and stress-induced IBS.

The algorithm for the actions of a practicing physician was developed by WGO and published in 2009 (

). If a patient is under 50 years of age with typical symptoms, no signs of alarm, a low incidence of parasitic infections and celiac disease in the population and no diarrhea, and no changes in the results of routine routine tests (complete blood count), the likelihood of IBS in this patient is so high that there is no need to conduct other examinations [20].

In the presence of persistent diarrheal syndrome, a high incidence of celiac disease or parasitic diseases, it is necessary, respectively, to conduct tests for celiac enteropathy, stool analysis to detect parasitic diseases and colonoscopy (for chronic diarrheal syndrome). In the absence of deviations from normal values, the diagnosis of IBS will be most likely.

Chronic abdominal pain syndrome with gastrointestinal transit disturbances, characteristic of IBS, is similar to the symptoms that occur with enteropathies (gluten, lactase, parasitic), colorectal cancer, microscopic, parasitic colitis, diverticulitis and some gynecological diseases: endometriosis, ovarian cancer. This is due to a single visceral mechanism of pain, which is often accompanied by its radiating genesis, which makes it even more difficult to determine the localization of the pathological process [17].

Relieving chronic abdominal pain is a serious independent problem, since not only elimination, but even an attempt to establish the main cause of its occurrence is not always possible. Considering that pain is often combined, in real practice it is often necessary to use a combination of various means.

One of the approaches to relieving visceral pain is the removal of muscle spasm, which is a universal mechanism of smooth muscles to respond to any pathological influences, which inevitably leads to excitation of nociceptors located in the muscular layer of the gastrointestinal tract [1–4, 18].

The group of antispasmodic drugs is diverse and quite heterogeneous in terms of the mechanism of action and point of application, since a rich receptor apparatus takes part in the contraction of muscle fiber, and this process itself is complex and multicomponent. Thus, drugs that suppress muscle fiber contraction can exert their effect in the following way:

- block the transmission of nerve impulses to muscle fibers (M-anticholinergics - atropine, platiphylline, hyoscine butyl bromide (Buscopan));

- suppress the opening of Na+ channels and the entry of Na+ into the cell (sodium channel blockers - mebeverine);

- suppress the opening of Ca+ channels and the flow of Ca+ from the extracellular space into the cytoplasm and the release of K+ from the cell - the initial stage of repolarization (calcium channel blockers - pinaveria bromide, otilonium bromide);

- suppress the activity of phosphodiesterase, the breakdown of cAMP, thereby blocking the energy processes of the muscle cell (phosphodiesterase blockers - alverine, drotaverine, etc.);

- act through serotonergic receptors, disrupting the regulation of ion transport;

- act on opioid receptors (trimebutine);

- influence oxidases (nitroglycerin and nitrosorbide).

The prescription of each drug must be justified from the standpoint of effectiveness and safety. The more selective the drug, the fewer systemic side effects it has.

Of all the selective antispasmodic drugs, the anticholinergic quaternary ammonium compound hyoscine butyl bromide (Buscopan) has been used the longest in Europe. The drug was first registered in Germany in 1951, and currently it is one of the most studied experimentally and clinically and selective antispasmodic drugs for the gastrointestinal tract. The most important pharmacological properties of hyoscine butylbromide are its dual relaxing effect through selective binding to muscarinic receptors located on the visceral smooth muscles of the gastrointestinal tract, and the parasympathetic effect of blocking nerve ganglia through binding to nicotinic receptors, which ensures selectivity of suppression of gastrointestinal motility.

Hyoscine butyl bromide, due to its high affinity for muscarinic and nicotinic receptors, is distributed mainly in the muscle cells of the abdominal and pelvic organs, as well as in the intramural ganglia of the abdominal organs. Because the drug does not cross the blood-brain barrier, the incidence of systemic anticholinergic (atropine-like) adverse reactions with hyoscine butyl bromide is very low and similar to placebo. Therefore, the feasibility of using this drug is obvious and proven to relieve pain of the visceral component of any origin [1, 3, 18, 19].

The onset of effect when taking Buscopan orally is approximately 30 minutes; duration of action is 2–6 hours. After a single oral administration of hyoscine butyl bromide in doses of 20–400 mg, average peak plasma concentrations are reached after approximately 2 hours. The half-life of the drug after a single oral dose of 100–400 mg ranges from 6.2 to 10.6 hours. Recommended oral dose: 10–20 mg 3–5 times daily. There is also a dosage form of Buscopan in rectal suppositories.

Published in 2006, a comparative placebo- and paracetamol-controlled study of the effectiveness and tolerability of hyoscine butylbromide in the treatment of recurrent cramping abdominal pain, conducted at 163 clinical centers under the leadership of such famous gastroenterologists as S. Müller-Lissner and G. N. Tytgat , included 1935 patients. It showed high efficacy and safety of hyoscine butyl bromide for recurrent abdominal pain [14].

Evidence of the antispasmodic effect of hyoscine butylbromide is the improvement in the results of instrumental examination of the intestine during endoscopic and x-ray examination, which is demonstrated by both an increase in the intestinal lumen and visualization of polyps, diverticula, as well as less pain during manipulations [11, 15].

An example of effective relief of abdominal pain with antispasmodics is their use in IBS [12].

A meta-analysis conducted by T. Poynard et al demonstrated that many antispasmodic drugs individually (mebeverine, cimetropium bromide, trimebutine, otilonium bromide, hyoscine butyl bromide, pinaveria bromide) and the entire group of antispasmodics (OR 2.13; 95% CI 1 .77–2.58) is more effective than placebo in the treatment of IBS pain [16]. Thus, the likelihood of improvement with the use of hyoscine butylbromide in the treatment of IBS is 1.56 times higher (95% CI 1.14–2.15) than with placebo. A number of studies have shown that, in addition to the antispasmodic effect, the good analgesic effect of Buscopan may also be associated with a decrease in the threshold of visceral hypersensitivity, which plays an important role in the pathogenesis of IBS [10].

Antispasmodics with proven effectiveness in the treatment of IBS from the point of view of the special American Gollege Gastroenterology (ACG) are hyoscine butyl bromide, cimetropium bromide, pinaveria bromide and peppermint oil. These drugs can relieve pain or discomfort associated with IBS [5].

Antispasmodics not only relieve pain, but also help restore the passage of contents and improve blood supply to the organ wall. Their administration is not accompanied by direct interference with the mechanisms of pain sensitivity and does not complicate the diagnosis of acute surgical pathology.

Of course, an important place in the relief of pain not only of parietal origin, but also of visceral and psychogenic origin is given to analgesics. The World Health Organization has proposed the following step-by-step approach to pain relief: 1st step - non-opioid analgesics, 2nd step - adding soft opioids, 3rd step - opioid analgesics. Among non-opioid analgesics, it is preferable to prescribe paracetamol due to fewer side effects on the gastrointestinal tract. A number of studies have shown a good effect for pain relief when combining the antispasmodic hyoscine butyl bromide with the analgesic paracetamol [13].

Sometimes it is necessary to use direct analgesics in case of functional diseases, in particular in IBS. The prescription of opiates should be avoided in every possible way, since with such chronic conditions there is a high risk of developing addiction and dependence. Such cases are described in the literature and are called “narcotic bowel syndrome” (intestinal syndrome caused by narcotic drugs). The criteria for this condition include chronic or often recurrent pain that progresses over time, which cannot be explained by a specific pathology, the relief of which requires large doses of narcotic drugs, which increases with the abolition of opiates and is quickly relieved with their use [8, 9].

The effect of antidepressants to potentiate and enhance the analgesic effect of other drugs is well known and proven. Taking into account the presence of a psychogenic mechanism of pain in functional diseases, clinically identified psycho-emotional characteristics of patients (tendency to depression, high levels of anxiety), the interest in psychotropic drugs for IBS is understandable. A recently published systematic review, although highlighting flaws in some study designs, provided evidence to support the use of antidepressants (both tricyclics and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) for IBS (amitriptyline 10–75 mg/day at bedtime; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: paroxetine, 10–60 mg/day, citalopram, 5–20 mg/day) [6, 20].

Explaining the genesis of symptoms and, above all, abdominal pain, taking into account the level of education, social status of the patient, and establishing a trusting, empathetic relationship between the doctor and the patient is effective in relieving symptoms [7].

Nutritional adjustments to reduce pain and relieve other symptoms should be used with some caution so as not to cause nutritional problems in the patient (deficiency of microelements, vitamins, other nutritional ingredients).

There is no convincing connection between abdominal pain and other symptoms of IBS. The use of drugs effective for relieving various disorders in IBS did not affect the severity of pain. In the presence of IBS with constipation, various classes of laxatives, fiber and other volume-forming drugs are used. A good evidence base exists for osmotic laxatives (lactulose preparations, polyethylene glycol in individual dosages). To speed up the normalizing effect on passage through the gastrointestinal tract in IBS with constipation, irritating laxatives (Dulcolax, etc.) can be prescribed in short courses. For the treatment of IBS with constipation in women, it is possible to use a selective activator of C-2 chloride receptors - lubiprostone [6]. There is evidence of the advisability of using the probiotic strain Bifidobacterium lactis DN-173 010 in order to accelerate intestinal transit.

The main drug for the treatment of IBS with diarrhea is loperamide, which requires individual dosage selection. For severe diarrheal syndrome in women, the serotonergic receptor antagonist (5-HT3)-alosetron has been registered for use in a number of countries [6, 20]. To reduce gas formation, sorbents and other defoamers are used, and some recommendations also call the antibiotic rifaximin (400 mg 3 times a day).

Some effects on improving the general condition and reducing pain were demonstrated by the antagonist of serotonergic receptors (5-HT3) - alosetron (in IBS with diarrhea syndrome), the selective activator of C-2 chloride receptors - lubiprostone (in women with constipation) and the probiotic strain Bifidobacterium infantis 35624 .

To relieve pain and other symptoms in functional pathology, in particular in IBS, a variety of therapy methods are used, including psychological ones: cognitive/behavioral therapy, relaxation methods, hypnosis. The ACG states that psychological therapies including cognitive therapy, dynamic psychotherapy and hypnotherapy are more effective in relieving common IBS symptoms than standard treatments. The attitude towards herbal medicine and acupuncture in general today is optimistically restrained.

The course of any pathology and especially IBS is largely influenced by both the patient’s personal characteristics (attitude to treatment, level of anxiety and degree of trust/distrust in medical manipulations, the presence of chronic traumatic situations, individual emotional characteristics, as well as mental illness), and the behavior of the medical professional. staff (the ability to establish contact and trust, the ability to provide psychological support to the patient). An important point that always increases the patient’s confidence in the doctor is the rapid relief of pain. Therefore, the choice of drugs must be made competently and in a timely manner.

Literature

- Baranskaya E.K. Abdominal pain: clinical approach to the patient and treatment algorithm. The place of antispasmodic therapy in the treatment of abdominal pain // Farmateka. 2005. No. 14.

- Wiley J. Assessment and meaning of abdominal pain. Chapter 1. In the book: J. Henderson. Pathophysiology of the digestive organs. St. Petersburg: Nevsky Dialect, 1997. 275 p.

- Livzan M.A. Pain syndrome in gastroenterology - treatment algorithm // Medical advice. 2010. No. 3–4. pp. 68–70.

- Shulpekova Yu. V., Ivashkin V. T. Symptom of visceral pain in pathology of the digestive organs // Doctor. 2008. No. 9. pp. 12–16.

- Brandt LJ, Chey WD, Foxx-Orenstein AE, Schiller LR, Schoenfeld PS, Spiegel BM, Talley NJ, Quigley EM American College of Gastroenterology Task Force on Irritable Bowel Syndrome An evidence-based position statement on the management of irritable bowel syndrome // Am J Gastroenterol. 2009, Jan; 104, Suppl 1: S1–35.

- Camilleri M. Review article: new receptor targets for medical therapy in irritable bowel syndrome // Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010, Jan; 31 (1): 35–46.

- Camilleri M. Evolving concepts of the pathogenesis of irritable bowel syndrome: to treat the brain or the gut // J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009, Apr; 48, Suppl 2: S46–48.

- Drossman DA Severe and refractory chronic abdominal pain // Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008, vol. 6, no. 9, pp. 978–982.

- Grunkemeier DMS, Cassara JE, Dalton CB, Drossman DA The narcotic bowel syndrome: clinical features, pathophysiology and management // Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007; No. 5; 1126–1139.

- Khalif IL, Quigley EM, Makarchuk PA, Golovenko OV, Podmarenkova LF, Dzhanayev YA Interactions between symptoms and motor and visceral sensory responses of irritable bowel syndrome patients to spasmolytics (antispasmodics) // J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009, Mar; 18 (1): 17–22.

- Lee JM, Cheon JH, Park JJ, Moon CM, Kim ES, Kim TI, Kim WH Effects of Hyosine N-butyl bromide on the detection of polyps during colonoscopy // Hepatogastroenterology. 2010, Jan-Feb; 57 (97): 90–94.

- Longstreth G., Thompson W., Chey W., Houghton L., Mearin F., Robin C. Spiller. Functional Bowel Disorders // Gastroenterology. 2006; 130:1480–1491.

- Mertz H. How effective are oral hyoscine butylbromide and paracetamol for the relief of crampy abdominal pain // Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007, Jan; 4 (1): 10–11.

- Mueller-Lissner S., Tytgat GN, Paulo LG, Quigley EM, Bubeck J., Peil H., Schaefer E. Placebo- and paracetamol-controlled study on the efficacy and tolerability of hyoscine butylbromide in the treatment of patients with recurrent abdominal cramps pain // Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006, Jun 15; 23 (12): 1741–1748.

- Misra SP, Dwivedi M. Role of intravenously administered hyoscine butyl bromide in retrograde terminal ileoscopy: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial // World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Mar 28;13(12):1820–1823.

- Poynard T., Regimbeau C., Benhamou Y. Meta-analysis of smooth muscle relaxants in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome // Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001; 15: 355–361.

- Spiegel B., Bolus R., Harris LA, Lucak S., Naliboff B., Esrailian E., Chey WD, Lembo A., Karsan H., Tillisch K., Talley J., Mayer E., Chang L. Measuring irritable bowel syndrome patient-reported outcomes with an abdominal pain numeric rating scale // Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009, Dec 1; 30 (11–12): 1159–1170.

- Tytgat GN Hyoscine butylbromide: a review of its use in the treatment of abdominal cramping and pain // Drugs. 2007; 67(9):1343–1357.

- Tytgat GN Hyoscine butylbromide — a review on its parenteral use in acute abdominal spasm and as an aid in abdominal diagnostic and therapeutic procedures // Curr Med Res Opin. 2008.

- WGO Practice guideline - Irritable bowel syndrome: a global perspective. April 2009.

M. F. Osipenko , Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor S. I. Kholin , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor A. N. Ryzhichkina , Candidate of Medical Sciences, Associate Professor Novosibirsk State Medical University, Novosibirsk

Contact information for authors for correspondence